As we age, we get inflexible, or at least that’s the perception of young people. We oldsters have a reputation for liking our own bathrooms, our own routines, our own way of doing things and our own beds. (When I gratefully crawled into mine after 17 nights away, I actually spoke to the bed.)

I don’t want to become unbending and am consciously trying to emulate the examples I know who live their lives with a great deal of give. Standing strong for moral beliefs is one thing, but being immovable on everything else results in a rigid life no one wants to be around. Even on the issue of right and wrong, listening to another point of view is a valuable (and attractive) M.O.

Nate was an example of someone who came to the end of his childhood fairly sure he knew the “right” way to do things. The way he figured it, GM was the place to buy cars, the Lutheran Church was the place to worship and Brooks Brothers was the place to shop. At the age of 17, he thought deviating from those and other standards translated into foolishness.

Then he left home for Northwestern University where life opened up new ways to view people, places and things. All of us look back and see signposts of importance marking our way. None of us leaves our family of origin (whether for college or another adventure) without quickly finding ourselves jamming a big post into the ground next to life’s path right then, which is why it’s important to leave home.

After passing that marker, Nate came to another big one when he met me. A signpost got mowed down when that happened, because opposites attract with extraordinary impact. Without that, we would have chosen opposite forks in the road.

So, if we were to end up together, Nate had to adapt. I didn’t drive a General Motors car, belong to the Lutheran Church or shop at Brooks Brothers. At that road marker he chose to step over many of his former beliefs, sizing them up as family traditions rather than life’s only way. Without that mental shift, he couldn’t have justified dating someone like me. With it, he could plant a new signpost and keep going.

That’s how life is for all of us. We grow, change and see things differently as time passes, hopefully practicing inclusivity rather than exclusivity. Looking back over 43 years since Nate and I met on a blind date, I see his life marked by a display of adaptability as he willingly rearranged the life markers he had once planned.

He grew into a fresh outlook in virtually every category including who he married, where he lived, whether or not he became a father, how many children he had, how he made money, how he spent it, and yes, what he drove, where he attended church and where he shopped. New points of view were not garnered grudgingly but came about with reflection and a consideration for the other fork in the road. But once he chose, he didn’t turn around.

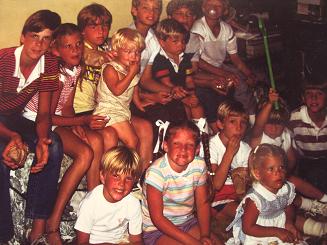

This photo was taken on a Sunday afternoon in a tiny summer cottage with a roomful of lively children swirling nearby. (See below.)

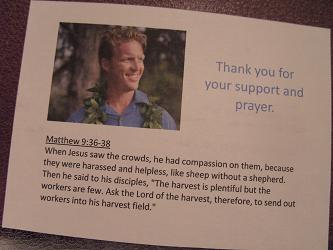

To me it’s a picture of Nate’s adaptability. Had he lived longer, I believe he would never have stopped adapting. His response to terminal pancreatic cancer was proof of that. When that road sign appeared, he modified his point of view in a way that demonstrated new heights of flexibility, because it led to the most significant marker of his life: death.

As different as people’s lives are from one another, no set of signposts is identical, but we’ll all end at the same marker as Nate did. It might have a different size and shape, a different way of being planted next to the path, but we’ll all end there. Rather than it being a dead-end, however, it opens the way to the last post, eternity.

Nate won’t pass any more markers or be presented with any more demands for adaptability. He’s moved past the biggest and best landmark of them all into God’s prepared home, and he’s done traveling.

“Blessed is the man whose strength is in Thee, in whose heart are the highways to Zion.” (Psalm 84:5)