I’m about to sign a sheet of 8½ x 11 paper with strange words on it: incised, polished, beveled, sawn, washed, sandblasted. It’s a verbal description of Nate’s cemetery headstone.

Although he died 14 months ago, we weren’t able to focus on a grave marker until the one year anniversary. When we visited the cemetery then, suddenly it seemed imperative to order a headstone. As Nelson said, the one scriptural reference to an unmarked grave is negative: “Woe to you! For you are like unmarked graves, and people walk over them without knowing it.” (Luke 11:44)

As we stood at the foot of Nate’s grave, memories washed over us, and though it’s difficult to design a headstone, we all wanted to get it done. After discussing the possibilities with cemetery personnel then revisiting the site, we went home and put pen to paper.

Our M.O. was to join Nate’s grave to the six family plots adjacent to his. My paternal grandfather, who died ten years before I was born, was the purchaser of the original plot when his family unexpectedly needed a grave. Their little William was only 20 months old when he died of pneumonia, an illness cured by antibiotics today. His name is third-down on the stone, a strong declaration by his parents that he should have died after both of them.

William’s funeral took place at Rosehill Cemetery on a snowy December day, surely the saddest event in this young family’s history. My father, William’s oldest sibling, was 12 at the time, old enough to remember the tiny casket and his parents’ anguish. William’s father arranged to have a photograph taken of their deceased toddler before his burial, the only picture of the son they knew so briefly.

But this family’s story further saddens. The second name carved on the Johnson headstone is William’s mother, who died of TB 15 months after her baby, leaving a widower with three children. These courageous people are a group we want to publically be connected to by designing our nearby stone in similar fashion.

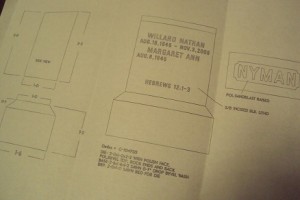

This week the cemetery envelope arrived in my mailbox. Knowing it contained a sketch of our stone, I waited to open it until I could put the visual into my head. Would it be difficult to look at it? Would it be a shock to see my own name there also? Would we be satisfied with our design?

Yes to all of that, difficult, shocking, but also satisfying. We made only one addition, a phrase of Scripture beneath the names as a testimony to the important role Jesus Christ played in the lives of those buried there.

After the headstone has been installed, I’ll eagerly look for the opportunity to rest my hand on its polished granite, look at my children and say (just as my folks said), “Someday you’ll bury me here, too. But remember, it’ll be a good day, because I’ll be with Jesus.” I’ll point to the letters carved in stone that are from their father’s favorite Scripture, reminding them to keep their eyes fixed on Jesus.

After all, that’s the best possible guidance for any heartbroken person seated in a cemetery in front of a descending casket.

“Let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us, fixing our eyes on Jesus…” (Hebrews 12:1b-2a)