In the morning when I apply mascara to my lifeless eyelashes I wonder, “Is this necessary?”

I don’t mean whether or not it’ll make me look better but whether or not it’ll be cried off at some point before nightfall. Daily weeping over missing Nate has stopped, although I can “lose it” at any time. My widow warriors tell me that may go on for years, but the spaces between break-downs will get longer and longer. Their counsel is true.

Today my mascara would have been better left in the tube. As I sat down with my cholesterol-lowering bowl of oatmeal, I decided to reread a few of the many emails my girls printed out for me long ago, at my request. I had asked them to print out messages “from the beginning” when we’d just received Nate’s pancreatic diagnosis.

Although he and I had spent time during those early days of adjustment last September reading the emails together, that time period is only a blur. I’ve been wanting to re-absorb the words of our precious friends in those messages for quite awhile. I set the thick stack of 8½ x 11 pages on the table, intending to look at one or two whenever I got the chance. There were hundreds of them, a treasure trove of love and a war chest of pertinent Scriptures.

The very first message was from our daughter Linnea expressing shock, sadness, disappointment, confusion, and by the end, total abandon to whatever God decided to do with her father and his family. It was hard to get through her words, but I managed. The second was from our son Nelson, simply one Bible verse: “Now to Him who is able to do immeasurably more than all we ask or imagine, according to His power that is at work within us, be glory in the church and in Christ Jesus throughout all generations for ever and ever! Amen!” (Ephesians 3:20-21) At that point, I was dabbing at my eyes.

The third email was from our son Hans’ parents-in-law in faraway England, sent two days after the diagnosis. Sarah wrote, “Hans and Katy are clinging to each other and have the comfort and closeness of Baby Nicholas, who smiles lovingly at them and cheers the sad moments. We’ll do our very best to support Hans, but he understandably wants to be with you. We will all be praying for a successful application to the Home Office.” This resurrected the tale of how God dramatically moved a mountain of snarled red tape to get Hans and his family to us in record time. [10/5/09 blog post: “Then God stepped in.”]

Hans’ father-in-law wrote, “There are lots of tears here, lots of questions, but still the knowledge that Somebody knows how this all fits together, even if in our moments of weakness we each lose the plot for a while.” And my sniffing began in earnest.

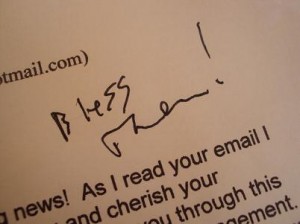

When I came to the fourth message from Pastor Lutzer and Rebecca, I had to get the Kleenex box. There on top of their two page email was Nate’s loopy handwriting of words written two days after his terminal diagnosis: “Bless them!” I must have printed the email for him to read privately, and as he sometimes did, he pulled out his pen and responded. His comment was written next to this statement from Rebecca: “As I read your email, I burst into tears…”

…as did I. And that was enough reading (and mascara) for today.

“There is no one like the God of Israel. He rides across the heavens to help you, across the skies in majestic splendor. The eternal God is your refuge, and his everlasting arms are under you.” (Deuteronomy 33:26-27a)