Twenty-ten is the year of the census. We’ve all received survey forms, and our government’s goal is to count every citizen. It’s nice to know we count, at least once every ten years.

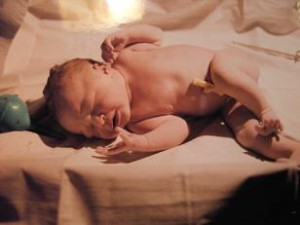

At the beginning of our lives we all count, too. As our parents announced our names, they were recorded on a document even more official than a census form. Our birth certificates follow us through life, and we often find ourselves needing to pull them from the file cabinet to prove who we are.

I remember needing our firstborn’s birth certificate to register him for kindergarten in a public school. As it turned out, we used a Christian school instead, but had he gone to the public kindergarten, legal proof of age was essential. When you’re five years old, your birth certificate is the only official thing you’ve got.

We use birth certificates when it’s time to get a social security card, a driver’s permit, a driver’s license or an official ID card. They’re required again when applying for passports and also to get a marriage license, assuring the bride and groom are of legal marrying age. Birth certificates vouch for us in name, age, parentage and citizenship, awarding us all the rights in each of those categories.

At the end of our lives we each get another important document, a death certificate. This, too, becomes official and of permanent importance, the original filed with the state in which a person dies. I remember my deep sadness in sitting with the Hospice nurse who came to our Michigan home the evening Nate died, to fill out his death certificate. She made the official pronouncement that his life had ended and signed the paper.

As with a birth, a death is documented carefully but includes far more information than a birth certificate. In addition to name, address, date and time, it includes social security number, ancestry, military record, race, education, occupation, where the person died, who was present, whether or not a doctor was there, the reason for the death, what happened to the body and other facts.

If someone dies at home without Hospice care, the police arrive in squad cars. They bring detectives who legally must question the sorrowful spouse to learn if there was wrong-doing in the death, adding incredible strain to an already distressing situation. The body is taken away in a body bag by a coroner rather than on a stretcher by a representative of a funeral home, but this is official death certificate procedure.

Birth and death certificates bookend the whole of life on earth. We all start at one document and end at the other. Our little grandson Nicholas, born in the UK and receiving his birth certificate there, automatically became a British citizen, just as children born in the US automatically become American citizens. His parents worked hard, however, to also secure American citizenship for Nicholas, since Hans is still a citizen of the US. This privileged baby had a passport picture taken before he could even sit up and pose, but dual citizenship in the two most powerful nations on the globe is a valuable commodity.

I have dual citizenship, too, although not in two countries. Although I’m an American, I also have citizenship in heaven, secured and written on a document far more important than any manuscript on file in our 50 states. My name is written in what the Bible calls the Lamb’s Book of Life, God’s record of everyone who embraces Jesus as the only way to heaven.

Nate’s name is written in that book, too, which is the reason he’s happily living in paradise today. And although birth and death certificates are supremely important on this earth, when all is said and done, the Lamb’s Book of Life will trump them all.

Referring to God’s eternal city: “Nothing impure will ever enter it, nor will anyone who does what is shameful or deceitful, but only those whose names are written in the Lamb’s book of life.” (Revelation 21:27)